Response to The Economist

In the Schumpeter column of The Economist on ‘Asian Innovation’, 24 March, 2012, the Economist argues ‘frugal ideas are spreading from East to West’. I’d like to take this opportunity to clarify and dispel some notions of frugal innovation as presented by the Economist articles.

Since the Economist’s seminal special report espousing frugal innovation in April 2010, there tends to be a focus on purely cost reduction through component redesign or the stripping of superfluous features to a level of basic needs. While component innovation is important, I’ve found, based on interviews of many of the “frugal innovators” exemplified in the Economist articles, that they equally embrace modular, architectural, and business model innovation.

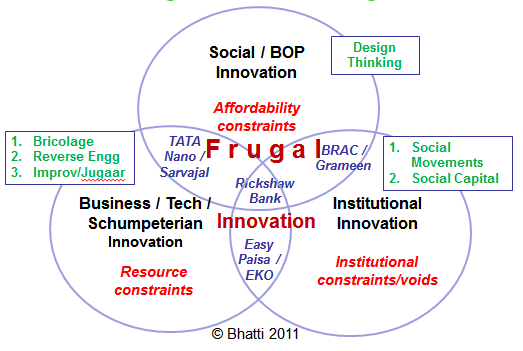

I have proposed a theory of frugal innovation which argues that frugal innovation isn’t being practised solely within the Schumpeterian domain of technology innovation, but inevitably overlaps and extends into the boundaries of institutional innovation and social innovation. It is in those intersections that hold the sweet spot which characterizes the true nature of frugal innovation, one that transcends a new value proposition based on cost or a specific marketing strategy.

This confluence of technology, institutional, and social innovation is necessary given the unusual contexts of emerging markets marked by resource constraints, institutional voids or even complexities, and large populations with affordability constraints. So simply put, frugal innovation provides functional solutions through few resources within complex or extreme contexts for the many who have little means.

Given local institutional contexts, frugal innovation discovers new business models, reconfigures value chains, and redesigns products to serve users who face extreme affordability constraints, in a scalable and sustainable manner. It involves overcoming or tapping resource constraints and institutional voids and complexities to create more inclusive markets (Bhatti, 2011).

So there is potential to demonstrate that this is a new kind of innovation process which leverages the challenges of institutional and resource challenges to debunk heavy R&D investment claims, and achieve profitability from underserved consumers. It is different from the standard innovation approach predominantly practiced in more developed contexts.

But to what degree are the two different, is a question I am in the middle of finding answers to.

Research Summary

I study innovation in emerging markets, contexts marked by institutional voids, resource scarcity, and affordability constraints. My DPhil (PhD) programme’s broad research question is “How do institutionally complex and resource constrained environments affect the discourse in innovation and the practise thereof?” I look at the particular case of emerging markets and therein the emerging field of ‘frugal innovation’. I focus on the rise of talk, practices, and policy about ‘frugal innovation’, a trend questions prevalent notions of innovation — on what is innovation, where it stems from (sources), whom to target (users), how best to achieve (design process), and how it spreads (diffusion).

This research entails understanding how localization and globalization processes are shaping innovation in and for emerging and developing market economies. Innovators in emerging markets have to devise low cost strategies to either tap or circumvent institutional voids and resource limitations to innovate, develop and deliver products and services to low income users with little purchasing power, often at mass scale and arguably in a sustainable manner. Hence, two main challenges persist in emerging nations for innovation and entrepreneurship: First is the issue of dealing with complex institutional contexts (Mair, Marti, & Ventresca 2012), institutional voids (Khanna and Palepu 1997 and others) and resource constraints and second is the issue of addressing the needs of the bottom of the pyramid i.e. the largest and poorest socio-economic segment of the population (Prahalad 2005). Despite institutional voids or complexities, emerging market entrepreneurs and firms are producing innovations which are resolving their local needs, and at the same time scaling to neighboring developing nations and even beyond to developed markets (Khanna 2008).

Through field work, interviews, and archival data, I am revealing how actors in the private, public, and community sectors are creating the market for frugal innovations — affordable, high value and sustainable solutions for local problems of global concern, often in complex environments where resources are unavailable or hard to control. These range widely in terms of core technology, focus, and impact. To date, I have inductively addressed why this emerging organizational field is gaining traction, how the space is being negotiated, and how to operationalize the practice of frugal innovation towards future deductive empirical research.

- Theory of Frugal Innovation

Based on thus far 30 plus interviews and five focus groups as well as over 150 documentary evidence of innovation from real ventures, I find that frugal innovation spans the boundaries across social, technical and institutional innovations to carve out a unique space that is enabling the development of a new field within innovation studies. Further, I find that ‘frugal’ is neither cheap nor substandard, but rather uses market forces to provide for under-served populations in the most efficient and sometimes sustainable manner. Social entrepreneurs, MNCs, communities, and states alike are involved in this market building and field generation activity which leads to as many questions as answers.

What is happening in emerging markets?

It is often maintained that firms from developed nations maintain a distant edge in innovation capabilities as compared to those from developing or emerging nations. But is the West actually leading the East in innovation?

We are not seeing just any standard innovation in emerging markets. I draw your attention to products such as a 2K pound Tata Nano car, 1000 dollar GE ECG machine, 100 dollar OLTPC laptop, or 10 pound Nokia solar powered mobile phone. These are only some of the low-cost yet high quality products emanating from emerging market opportunities through a phenomenon which is gaining popularity in emerging markets, particularly India and China, called FRUGAL INNOVATION.

In the latest Bloomberg BusinessWeek’s 50 Most Innovative Companies rankings, for the first time since the annual rankings were launched in 2005, the majority of corporations are based outside the U.S and the new global leaders are coming out of mainly Asia. Entrepreneurs, leaders and managers understand how to manage and generate innovation for sustained competitive advantage. In terms of executive leader mindset in China, 95% of executives said innovation was the key to economic growth, while 90% and 89% of respondents in South America and India, respectively, agreed. Comparatively lower, in the U.S., only 72% said innovation was important.

Popularized by special report by The Economist (2010): “…”frugal innovation” or “constrain-based innovation” is not just a matter of exploiting cheap labour (though cheap labour helps). It is a matter of redesigning products and processes to cut out unnecessary costs.” Further, researchers claim that frugal innovation is in deep contrast with products, services, and processes which are typically energy inefficient, raw material inefficient, and environmentally inefficient, often produced in the advanced developed economies.

Consumers in emerging markets are benefitting from frugal innovation. But will we all benefit? As the West looks to the East for ideas, frugal innovation from EMs could offer fresh ideas and new perspectives in cost minimization and innovation maximization to a world slowed down by the recent recession. What we learn from the East might help us to maintain a high standard of living without incurring escalating and debilitating costs to not only to our personal pockets but also to our natural environment.

Frugal Innovation Questions

Frugal innovation is a new phenomenon which is posed to rethink the innovation process!

Several questions remain unanswered for both academics and practitioners:

- What is frugal about frugal innovation?

- Is frugal innovation, innovation?

- How is it different or similar to standard innovation?

- What are the sources of frugal innovation? Who benefits?

- How does it relate to services and products?

- What is the design process for frugal innovation?

- Does cheap mean that it is low quality?

- Who is best at carrying out frugal innovation, local firms or MNCs?

The questions I am currently delving into as part of my PhD doctoral work are:

- What constitutes (frugal) innovation in or for emerging markets?

- What capabilities and core competencies are required to meet the needs of emerging market customers (i.e. frugally innovate)?

As my work progresses beyond the PhD, I aim to tackle supplementary questions such as:

- Are frugal innovation capabilities and core competencies unique to certain contexts and firms?

- How do emerging market firms differ from foreign firms in the capabilities to overcome contextual constraints in emerging markets?

- Do these capabilities and core competencies serve as a competitive advantage for firms?

What is frugal innovation? Definition

What is frugal innovation?

As a process frugal innovation discovers new business models, reconfigures value chains, and redesigns products to serve users who face extreme affordability constraints, in a scalable and sustainable manner. It involves either overcoming or tapping institutional voids and resource constraints to create more inclusive markets (Bhatti, 2011).

Simply, frugal innovation provides functional solutions through few resources for the many who have little means.

How is it different from standard innovation?

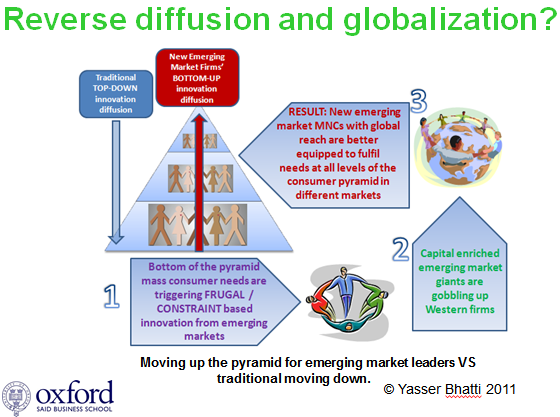

The general practice is to innovate for the top of the pyramid as there lies the greatest purchasing power with eventual trickle down effects. As such most design in Western markets relies on a ‘top down’ approach, targetting first the richer clientelle. Western practises use traditional (archaic) business and distribution models, rely on abundant resources (non-sustainable), incur costly product design and development, and result in high manufacturing costs which makes many science and technology innovations unaffordable for the bottom of the pyramid consumers.

In contrast, frugal innovation as is practised in emerging markets purposefully targets the bottom and then makes its way up to other levels to benefit all users. There is potential to demonstrate that this is a new kind of innovation process which leverages institutional voids and resource constraints, debunks heavy R&D investment claims, and achieves profitability from BOP consumers.

Why am I passionate about frugal innovation?

As an engineer my motivation stems from making so many people happy. As a social scientist, the phenomenon leads me to question and rethink our longheld understanding of innovation — like what is innovation, where does it stem from (sources), how to best do it (design process), and for whom is it (diffusion).

How does the context affect innovation?

On the input side you have to deal with the challenges of complex institutions or the lack thereof as well as resource constraints and on the output side the challenge of low affordability. For instance, regulatory regimes in the West may actually hinder BOP innovation while the lack thereof in EM could offer ground for creativity. If the USA is managed by lawyers then Asia is managed by engineers and technocrats. In the Eest regulations may hinder access to such devices, but in the East, such prohibitive regulatory institutions don’t exist in EM so this may be an enabling context. Not only that, scholars such as Christenson believe this may be a fertile ground for disruptive innovation and creative destruction.

Are frugal innovation and social entrepreneurship and innovation related?

The two are not mutually exclusive and nor is one a subset of the other. There can be overlapping concerns as frugal innovation and social enterprise commonly agree on who to benefit, but I believe they differ on how this is best achieved.

Social enterprise, to me, stems from a notion that the affluent, particularly those in the West, can promote development using business models that are self-sustaining. There exists contention on whether the profits from social enterprises can be issued to shareholders or should the profits be used solely for community development and reinvestment into growing the social enterprise.

In contrast, frugal innovation stems from unique circumstances in emerging markets given their vast populations with little yet growing means, few resources, and complex institutions or the lack thereof. Frugal innovation is a local phenomenon in emerging markets through which entrepreneurs try to make the most of what they control to fulfil local needs, needs which have been for too long neglected by mainstream businesses. There is no concern on how the profits are used or shared.

Having said that, “innovation” as a concept, a philosophy, and process is gaining popularity in for instance, South Asia, even more so than “social enterprise”. Many firms and universities are scrambling to formalize programmes in innovation, and guess what type of innovation is most relevant to them as well as doable within their reach? “Frugal innovation” –- They might not call it that, but many such efforts are structured around solving problems at a local and practical level and in a sustainable manner.

What is frugal about frugal innovation?

There are several dimensions to it not just limited to cost (please see diagram below), but the main theme is simplification in all aspects of process and end-result — something GE’s CEO Immelt calls magnificient simplification.

If its cheap, is it low quality?

On the contrary, it needs to be highly robust given the extreme environments in which the innovation functions. Further the innovation needs to be very intuitive to use and require very little servicing — what you might call “solutions for dummies”.

Services or products?

Both! In services there are examples of frugal innovation in communication, banking, energy, training, and education; among products examples lie in automobiles, medical devices, and housing. (Please see post on examples)

Who is best at frugally innovating, local firms or MNCs?

Foreign firms generally view institutional voids as challenges, have abundant or slack resources to the production process, and often target “up-scale” markets. Therefore, enabling drivers are missing to frugally innovate so standard innovation process is pursued. Local firm view institutional voids as opportunities, have fewer resources to feed into the production process, and are more inclined to target “Lower” or “BOP” markets. Since they experience enabling drivers to frugally innovate, they generate capabilities and core competences which are unique to frugal innovation. Collateral/complementary assets with interdependencies are missing in EM which open the way for disruptive innovation.

Perhaps it may not be one or the other — rather a joint venture of both would be the most fertile ground for frugal innovation.

Will frugal innovation become popular?

My hunch is that like the Toyota Production System that was adopted worldwide as Total Quality Management philosophy, frugal innovation will be the next integrated management philosophy to diffuse from the East to the West. The next big question will be whether this will give adopting firms a competitive advantage? Possibly not, because still no one does TPS better than Toyota!

Frugal-Reverse-Cost-BOP Innovation

CEO of GE Jeff Immelt calls the frugal innovation phenomenon reverse innovation. “If GE doesn’t master reverse (frugal) innovation, the emerging giants could destroy the company” (Immelt, Govindarajan, and Timble, 2009). Although there are several dimensions to frugal innovation, the overarching theme is simplification in process and outcome. There can be many connotations for “reverse” which are similar to frugal innovation in both process and outcome.

One, frugal or reverse innovation integrates specific needs of the bottom of the pyramid markets as a starting point and works backward to develop appropriate solutions which may be significantly different from existing solutions designed to address needs of upmarket segments (Silicon India, 2010). The context in which this innovation is seen occuring in lies in developing markets. Fu, Soete & Sonne (2010) claim that the innovation process itself is now likely to be reversed, starting with the design phase which will, to a large extent, be concerned with finding functional solutions for some of the particular BoP users’ framework conditions… (such as) a clear adaptation to the often poor local infrastructure facilities with respect to energy delivery systems, water access, transport infrastructure, digital access.

Two, there is a reverse process of diffusion among consumers. Innovation is often perceived in the developed world as technological revolutionary products tried and tested by innovators and early adopters (Rogers, 1962). Trendy and expensive products are accepted by the top of the pyramid first which then get trickled down to the masses or early and late majority consumers. Professional groups in the highest income bracket in society that constitute the “tip” of the income pyramid act as the early adopters and the first try-out group, contributing to the innovation monopoly rents of the innovating firm. But this “professional-use driven” innovation circle has been the main source for extracting innovation rents out of consumer goods that was considered “too long” (Fu et al, 2010). Hence, in frugal innovation we see a challenge to this notion of diffusion from the top to the bottom. Frugal innovation “reverses” the process of diffusion by targetting the early and late majority consumers and relies on profiting not from monopoly rents, but rather economies of scale rents. Eventually, all segments of the market benefit from the innovation. A prime example of this is mobile phone banking by Telenor in Pakistan and MPesa in Kenya wherein success has in these business models have been marked through adoption by rural BOP consumers before becoming popular in all segments rural and urban.

Three, we might see a trend in practices of innovation being adopted from the East to the West wherein Western practices had dominated thus far. Innovation is no longer formulated just in the West and exported to the developing world. Instead, many new innovations that are considered “frugal” will emanate from the emerging world and into the West (The Economist, 2010). Again, mobile phone banking and inexpensive and portable medical devices are emanating from emerging / developing markets but could find their way to mature markets.

I believe frugal holistically describes the phenomenon more aptly. Reverse innovation, to me, is based on a primary characteristic of the phenomenon which is bottom-up and East-to-West. Others have called this phenomenon “Cost” innovation (Li and Hang, 2010) and “BOP” innovation (Prahalad, 2005) which limits the definition to simply reduction in cost of outcome for a specific target market. Instead, frugal innovation embodies the frame of mind, philosophy, process, and purpose behind this phenomenon spanning from exploration to exploitation phases. More on this later!